Effects of 17β-Estradiol and Estrogen Receptor Antagonists on the ...

Estradiol and Estrogen kháng KATOIII

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from 17β-Estradiol)

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛstrəˈdaɪoʊl/ ES-trə-DYE-ohl[1][2] |

| IUPAC name

(8R,9S,13S,14S,17S)-13-Methyl-6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-decahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-3,17-diol

| |

| Other names

Estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol; 17β-Estradiol

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

| |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.022 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

| |

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| C18H24O2 | |

| Molar mass | 272.38 g/mol |

| -186.6·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Pharmacology | |

| G03CA03 (WHO) | |

| Oral, sublingual, intranasal, topical/transdermal, vaginal, intramuscular or subcutaneous (as an ester), subdermal implant | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| Oral: <5%[3] | |

| ~98%:[3][4] • Albumin: 60% • SHBG: 38% • Free: 2% | |

| Liver (via hydroxylation, sulfation, glucuronidation) | |

| Oral: 13–20 hours[3] Sublingual: 8–18 hours[5] Topical (gel): 36.5 hours[6] | |

| Urine: 54%[3] Feces: 6%[3] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Infobox references | |

Estradiol (E2), also spelled oestradiol, is a steroid, an estrogen, and the primary female sex hormone. It is named for and is important in the regulation of the estrous and menstrual female reproductive cycles. Estradiol is essential for the development and maintenance of female reproductive tissues such as the breasts, uterus, and vagina during puberty, adulthood, and pregnancy,[7] but it also has important effects in many other tissues including bone, fat, skin, liver, and the brain. While estrogen levels in men are lower compared to women, estrogens have essential functions in men as well. Estradiol is found in most vertebrates as well as many crustaceans, insects, fish, and other animal species.[8][9]

Estradiol is produced especially within the follicles of the female ovaries, but also in other endocrine (i.e., hormone-producing) and non-endocrine tissues (e.g., including fat, liver, adrenal, breast, and neural tissues). Estradiol is biosynthesized from cholesterol through a series of chemical intermediates.[10] One principal pathway involves the generation of 4-androstenedione, which is converted into estrone by aromatase and then by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase into estradiol. Alternatively, 4-androstenedione can be converted into testosterone, an androgen and the primary male sex hormone, which in turn can be aromatized into estradiol.

Biological function[edit]

Sexual development[edit]

The development of secondary sex characteristics in women is driven by estrogens, to be specific, estradiol.[11][12] These changes are initiated at the time of puberty, most are enhanced during the reproductive years, and become less pronounced with declining estradiol support after menopause. Thus, estradiol produces breast development, and is responsible for changes in the body shape, affecting bones, joints, and fat deposition.[11][12] In females, estradiol induces breast development, widening of the hips, a feminine fat distribution (with fat deposited particularly in the breasts, hips, thighs, and buttocks), and maturation of the vagina and vulva, whereas it mediates the pubertal growth spurt (indirectly via increased growth hormone secretion)[13] and epiphyseal closure (thereby limiting final height) in both sexes.[11][12]

Reproduction[edit]

Female reproductive system[edit]

In the female, estradiol acts as a growth hormone for tissue of the reproductive organs, supporting the lining of the vagina, the cervical glands, the endometrium, and the lining of the fallopian tubes. It enhances growth of the myometrium. Estradiol appears necessary to maintain oocytes in the ovary. During the menstrual cycle, estradiol produced by the growing follicle triggers, via a positive feedback system, the hypothalamic-pituitary events that lead to the luteinizing hormone surge, inducing ovulation. In the luteal phase, estradiol, in conjunction with progesterone, prepares the endometrium for implantation. During pregnancy, estradiol increases due to placental production. The effect of estradiol, together with estrone and estriol, in pregnancy is less clear. They may promote uterine blood flow, myometrial growth, stimulate breast growth and at term, promote cervical softening and expression of myometrial oxytocinreceptors.[citation needed] In baboons, blocking of estrogen production leads to pregnancy loss, suggesting estradiol has a role in the maintenance of pregnancy. Research is investigating the role of estrogens in the process of initiation of labor. Actions of estradiol are required before the exposure of progesterone in the luteal phase.[citation needed]

Male reproductive system[edit]

The effect of estradiol (and estrogens in general) upon male reproduction is complex. Estradiol is produced by action of aromatase mainly in the Leydig cells of the mammalian testis, but also by some germ cells and the Sertoli cells of immature mammals.[14] It functions (in vitro) to prevent apoptosis of male sperm cells.[15] While some studies in the early 1990s claimed a connection between globally declining sperm counts and estrogen exposure in the environment,[16] later studies found no such connection, nor evidence of a general decline in sperm counts.[17][18] Suppression of estradiol production in a subpopulation of subfertile men may improve the semen analysis.[19]

Males with certain sex chromosome genetic conditions, such as Klinefelter's syndrome, will have a higher level of estradiol.[20]

Skeletal system[edit]

Estradiol has a profound effect on bone. Individuals without it (or other estrogens) will become tall and eunuchoid, as epiphyseal closure is delayed or may not take place. Bone structure is affected also, resulting in early osteopenia and osteoporosis.[21] Also, women past menopause experience an accelerated loss of bone mass due to a relative estrogen deficiency.[22]

Skin health[edit]

The estrogen receptor, as well as the progesterone receptor, have been detected in the skin, including in keratinocytes and fibroblasts.[23][24] At menopause and thereafter, decreased levels of female sex hormones result in atrophy, thinning, and increased wrinkling of the skin and a reduction in skin elasticity, firmness, and strength.[23][24] These skin changes constitute an acceleration in skin aging and are the result of decreased collagen content, irregularities in the morphology of epidermal skin cells, decreased ground substance between skin fibers, and reduced capillaries and blood flow.[23][24] The skin also becomes more dry during menopause, which is due to reduced skin hydration and surface lipids (sebum production).[23] Along with chronological aging and photoaging, estrogen deficiency in menopause is one of the three main factors that predominantly influences skin aging.[23]

HRT, consisting of systemic treatment with estrogen alone or in combination with a progestogen, has well-documented and considerable beneficial effects on the skin of postmenopausal women.[23][24] These benefits include increased skin collagen content, skin thickness and elasticity, and skin hydration and surface lipids.[23][24] Topical estrogen has been found to have similar beneficial effects on the skin.[23] In addition, a study has found that topical 2% progesterone cream significantly increases skin elasticity and firmness and observably decreases wrinkles in peri- and postmenopausal women.[24] Skin hydration and surface lipids, on the other hand, did not significantly change with topical progesterone.[24] These findings suggest that progesterone, like estrogen, also has beneficial effects on the skin, and may be independently protective against skin aging.[24]

Nervous system[edit]

Estrogens can be produced in the brain from steroid precursors. As antioxidants, they have been found to have neuroprotective function.[25]

The positive and negative feedback loops of the menstrual cycle involve ovarian estradiol as the link to the hypothalamic-pituitary system to regulate gonadotropins.[26](See Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis.)

Estrogen is considered to play a significant role in women’s mental health, with links suggested between the hormone level, mood and well-being. Sudden drops or fluctuations in, or long periods of sustained low levels of estrogen may be correlated with significant mood-lowering. Clinical recovery from depression postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause was shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized and/or restored.[27][28]

Recently, the volumes of sexually dimorphic brain structures in transgender women were found to change and approximate typical female brain structures when exposed to estrogen concomitantly with androgen deprivation over a period of months,[29] suggesting that estrogen and/or androgens have a significant part to play in sex differentiation of the brain, both prenatally and later in life.

There is also evidence the programming of adult male sexual behavior in many vertebrates is largely dependent on estradiol produced during prenatal life and early infancy.[30] It is not yet known whether this process plays a significant role in human sexual behavior, although evidence from other mammals tends to indicate a connection.[31]

Estrogen has been found to increase the secretion of oxytocin and to increase the expression of its receptor, the oxytocin receptor, in the brain.[32] In women, a single dose of estradiol has been found to be sufficient to increase circulating oxytocin concentrations.[33]

Gynecological cancers[edit]

Estradiol has been tied to the development and progression of cancers such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer. Estradiol affects target tissues mainly by interacting with two nuclear receptors called estrogen receptor α (ERα) and estrogen receptor β (ERβ).[34][35] One of the functions of these estrogen receptors is the modulation of gene expression. Once estradiol binds to the ERs, the receptor complexes then bind to specific DNA sequences, possibly causing damage to the DNA and an increase in cell division and DNA replication. Eukaryotic cells respond to damaged DNA by stimulating or impairing G1, S, or G2 phases of the cell cycle to initiate DNA repair. As a result, cellular transformation and cancer cell proliferation occurs.[36]

Other functions[edit]

Estradiol has complex effects on the liver. It affects the production of multiple proteins, including lipoproteins, binding proteins, and proteins responsible for blood clotting.[citation needed] In high amounts, estradiol can lead to cholestasis, for instance cholestasis of pregnancy.

Certain gynecological conditions are dependent on estrogen, such as endometriosis, leiomyomata uteri, and uterine bleeding.[citation needed]

Estrogen affects certain blood vessels. Improvement in arterial blood flow has been demonstrated in coronary arteries.[37]

Biological activity[edit]

Estradiol acts primarily as an agonist of the estrogen receptor (ER), a nuclear steroid hormone receptor. There are two subtypes of the ER, ERα and ERβ, and estradiol potently binds to and activates both of these receptors. The result of ER activation is a modulation of gene transcription and expression in ER-expressing cells, which is the predominant mechanism by which estradiol mediates its biological effects in the body. Estradiol also acts as an agonist of membrane estrogen receptors (mERs), such as GPER (GPR30), a recently discovered non-nuclear receptor for estradiol, via which it can mediate a variety of rapid, non-genomic effects.[38] Unlike the case of the ER, GPER appears to be selective for estradiol, and shows very low affinities for other endogenous estrogens, such as estrone and estriol.[39] Additional mERs besides GPER include ER-X, ERx, and Gq-mER.[40][41]

ERα/ERβ are in inactive state trapped in multimolecular chaperone complexes organized around the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), containing p23 protein, and immunophilin, and located in majority in cytoplasm and partially in nucleus. In the E2 classical pathway or estrogen classical pathway, estradiol enters the cytoplasm, where it interacts with ERs. Once bound E2, ERs dissociate from the molecular chaperone complexes and become competent to dimerize, migrate to nucleus, and to bind to specific DNA sequences (estrogen response element, ERE), allowing for gene transcription which can take place over hours and days.

Estradiol is reported to be approximately 12 times as potent as estrone and 80 times as potent as estriol in its estrogenic activity.[42][43] As such, estradiol is the main estrogen in the body, although the roles of estrone and estriol as estrogens are said to not be negligible.[43]

Biochemistry[edit]

Biosynthesis[edit]

Estradiol, like other steroids, is derived from cholesterol. After side chain cleavage and using the Δ5 or the Δ4- pathway, Δ4-androstenedione is the key intermediary. A portion of the Δ4-androstenedione is converted to testosterone, which in turn undergoes conversion to estradiol by aromatase. In an alternative pathway, Δ4-androstenedione is aromatized to estrone, which is subsequently converted to estradiol.[45]

During the reproductive years, most estradiol in women is produced by the granulosa cells of the ovaries by the aromatization of Δ4-androstenedione (produced in the theca folliculi cells) to estrone, followed by conversion of estrone to estradiol by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Smaller amounts of estradiol are also produced by the adrenal cortex, and, in men, by the testes.[citation needed]

Estradiol is not produced in the gonads only, in particular, fat cells produce active precursors to estradiol, and will continue to do so even after menopause.[46] Estradiol is also produced in the brain and in arterial walls.

The biosynthesis of estradiol-like compounds has been observed in leguminous plants, such as Phaseolus vulgaris and soybeans.[relevant? ][47] where they are termed phytoestrogens. Thus, consumption may have oestrogenic effects. In light of this, consumption can be counterproductive to patients undergoing treatment for breast cancer, which usually includes depriving the cancer cells of estrogens.

Distribution[edit]

In plasma, estradiol is largely bound to SHBG, and also to albumin. Only a fraction of 2.21% (± 0.04%) is free and biologically active, the percentage remaining constant throughout the menstrual cycle.[48]

Metabolism[edit]

Inactivation of estradiol includes conversion to less-active estrogens, such as estrone and estriol. Estriol is the major urinary metabolite.[citation needed] Estradiol is conjugated in the liver to form estrogen conjugates like estradiol sulfate, estradiol glucuronide and, as such, excreted via the kidneys. Some of the water-soluble conjugates are excreted via the bile duct, and partly reabsorbed after hydrolysis from the intestinal tract. This enterohepatic circulation contributes to maintaining estradiol levels.

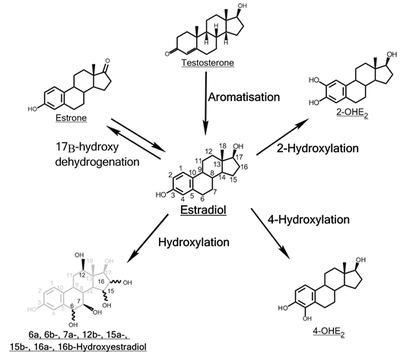

Estradiol is also metabolized via hydroxylation into catechol estrogens. In the liver, it is non-specifically metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP3A4, and CYP2C9 via 2-hydroxylation into 2-hydroxyestradiol, and by CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2C8 via 17β-hydroxy dehydrogenation into estrone,[49] with various other cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and metabolic transformationsalso being involved.[50]

Estradiol is additionally esterified into lipoidal estradiol forms like estradiol palmitate and estradiol stearate to a certain extent; these esters are stored in adipose tissue and may act as a very long-lasting reservoir of estradiol.[51][52]

Levels[edit]

Levels of estradiol in premenopausal women are highly variable throughout the menstrual cycle and reference ranges widely vary from source to source.[53] Estradiol levels are minimal and according to most laboratories range from 20 to 80 pg/mL during the early to mid follicular phase (or the first week of the menstrual cycle, also known as menses).[54][55] Levels of estradiol gradually increase during this time and through the mid to late follicular phase (or the second week of the menstrual cycle) until the pre-ovulatory phase.[53][54] At the time of pre-ovulation (a period of about 24 to 48 hours), estradiol levels briefly surge and reach their highest concentrations of any other time during the menstrual cycle.[53] Circulating levels are typically between 130 and 200 pg/mL at this time, but in some women may be as high as 300 to 400 pg/mL, and the upper limit of the reference range of some laboratories are even greater (for instance, 750 pg/mL).[53][54][56][57][58] Following ovulation (or mid-cycle) and during the latter half of the menstrual cycle or the luteal phase, estradiol levels plateau and fluctuate between around 100 and 150 pg/mL during the early and mid luteal phase, and at the time of the late luteal phase, or a few days before menstruation, reach a low of around 40 pg/mL.[53][55] The mean integrated levels of estradiol during a full menstrual cycle have variously been reported by different sources as 80, 120, and 150 pg/mL.[55][59][60] Although contradictory reports exist, one study found mean integrated estradiol levels of 150 pg/mL in younger women whereas mean integrated levels ranged from 50 to 120 pg/mL in older women.[60]

During the reproductive years of the human female, levels of estradiol are somewhat higher than that of estrone, except during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle; thus, estradiol may be considered the predominant estrogen during human female reproductive years in terms of absolute serum levels and estrogenic activity.[citation needed] During pregnancy, estriol becomes the predominant circulating estrogen, and this is the only time at which estetrol occurs in the body, while during menopause, estrone predominates (both based on serum levels).[citation needed] The estradiol produced by male humans, from testosterone, is present at serum levels roughly comparable to those of postmenopausal women (14-55 versus <35 pg/mL, respectively).[citation needed] It has also been reported that if concentrations of estradiol in a 70-year-old man are compared to those of a 70-year-old woman, levels are approximately 2- to 4-fold higher in the man.[61]

Measurement[edit]

In women, serum estradiol is measured in a clinical laboratory and reflects primarily the activity of the ovaries. As such, they are useful in the detection of baseline estrogen in women with amenorrhea or menstrual dysfunction, and to detect the state of hypoestrogenicity and menopause. Furthermore, estrogen monitoring during fertility therapy assesses follicular growth and is useful in monitoring the treatment. Estrogen-producing tumors will demonstrate persistent high levels of estradiol and other estrogens. In precocious puberty, estradiol levels are inappropriately increased.

Ranges[edit]

Individual laboratory results should always been interpreted using the ranges provided by the laboratory that performed the test.

| Reference ranges for serum estradiol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient type | Lower limit | Upper limit | Unit |

| Adult male | 50[63] | 200[63] | pmol/L |

| 14 | 55 | pg/mL | |

| Adult female (follicular phase, day 5) | 70[63] 95% PI (standard) | 500[63] 95% PI | pmol/L |

| 110[64] 90% PI (used in diagram) | 220[64] 90% PI | ||

| 19 (95% PI) | 140 (95% PI) | pg/mL | |

| 30 (90% PI) | 60 (90% PI) | ||

| Adult female (preovulatory peak) | 400[63] | 1500[63] | pmol/L |

| 110 | 410 | pg/mL | |

| Adult female (luteal phase) | 70[63] | 600[63] | pmol/L |

| 19 | 160 | pg/mL | |

| Adult female - free (not protein bound) | 0.5[65][original research?] | 9[65][original research?] | pg/mL |

| 1.7[65][original research?] | 33[65][original research?] | pmol/L | |

| Post-menopausal female | N/A[63] | < 130[63] | pmol/L |

| N/A | < 35 | pg/mL | |

In the normal menstrual cycle, estradiol levels measure typically <50 pg/ml at menstruation, rise with follicular development (peak: 200 pg/ml), drop briefly at ovulation, and rise again during the luteal phase for a second peak. At the end of the luteal phase, estradiol levels drop to their menstrual levels unless there is a pregnancy.

During pregnancy, estrogen levels, including estradiol, rise steadily toward term. The source of these estrogens is the placenta, which aromatizes prohormonesproduced in the fetal adrenal gland.

Medical uses[edit]

Chemistry[edit]

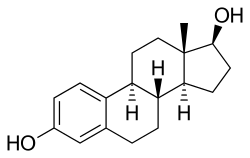

Estradiol is an estrane (C18) steroid.[66] It is also known as 17β-estradiol (to distinguish it from 17α-estradiol) or as estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17β-diol. It has two hydroxyl groups, one at the C3 position and the other at the 17β position, as well as three double bonds in the A ring. Due to its two hydroxyl groups, estradiol is often abbreviated as E2. The structurally related estrogens, estrone (E1), estriol (E3), and estetrol (E4) have one, three, and four hydroxyl groups, respectively.

History[edit]

The discovery of estrogen is usually credited to the American scientists Edgar Allen and Edward A. Doisy.[67][68] In 1923, they observed that injection of fluid from porcine ovarian follicles produced pubertal- and estrus-type changes (including vaginal, uterine, and mammary gland changes and sexual receptivity) in sexually immature, ovariectomized mice and rats.[67][68][69] These findings demonstrated the existence of a hormone which is produced by the ovaries and is involved in sexual maturation and reproduction.[67][68][69] At the time of its discovery, Allen and Doisy did not name the hormone, and simply referred to it as an "ovarian hormone" or "follicular hormone";[68] others referred to it variously as feminin, folliculin, menformon, thelykinin, and emmenin.[70][71] In 1926, Parkes and Bellerby coined the term estrin to describe the hormone on the basis of it inducing estrus in animals.[72][70] Estrone was isolated and purified independently by Allen and Doisy and Germanscientist Adolf Butenandt in 1929, and estriol was isolated and purified by Marrian in 1930; they were the first estrogens to be identified.[68][73][74]

Estradiol, the most potent of the three major estrogens, was the last of the three to be identified.[68][72] It was discovered by Schwenk and Hildebrant in 1933, who synthesized it via reduction of estrone.[68] Estradiol was subsequently isolated and purified from sow ovaries by Doisy in 1935, with its chemical structure determined simultaneously,[75] and was referred to variously as dihydrotheelin, dihydrofolliculin, and dihydroxyestrin.[68][76] In 1935, the name estradiol and the term estrogen were formally established by the Sex Hormone Committee of the Health Organization of the League of Nations; this followed the names estrone (which was initially called theelin, progynon, folliculin, and ketohydroxyestrin) and estriol (initially called theelol and trihydroxyestrin) having been established in 1932 at the first meeting of the International Conference on the Standardization of Sex Hormones in London.[72][77] Following its discovery, a partial synthesis of estradiol from cholesterol was developed by Inhoffen and Hohlweg in 1940, and a total synthesis was developed by Anner and Miescher in 1948.[68]

In 1931, Butenandt found that the benzoic acid ester of estrone had a prolonged duration of action.[78][79] Subsequently, Schwenk and Hildebrant synthesized estradiol benzoate from estradiol in 1933,[80][81] and estradiol benzoate was introduced by Schering-Kahlbaum for medical use via intramuscular injection under the brand name Progynon-B in 1936.[82] It was the first estrogen ester to be marketed,[83] and has since been followed by many additional esters, for instance estradiol valerate and estradiol cypionate in the 1950s.[84][85][86] Ethinylestradiol was synthesized from estradiol by Inhoffen and Hohlweg in 1938 and was introduced for oral use by Schering in the United States under the brand name Estinyl in 1943.[80][87] It remains widely used in combined oral contraceptives.[80]

Society and culture[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The name estradiol derives from estra-, Gk. οἶστρος (oistros, literally meaning "verve or inspiration"),[88] which refers to the estrane steroid ring system, and -diol, a chemical term and suffix indicating that the compound is a type of alcohol bearing two hydroxyl groups.

Estrogen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Estrogen | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Estradiol, the major estrogen sex hormone in humans and a widely used medication.

| |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Contraception, Menopause, hypogonadism, transgender women, prostate cancer, breast cancer, others |

| ATC code | G03C |

| Biological target | Estrogen receptors (ERα, ERβ, mERs (e.g., GPER, others)) |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D004967 |

| In Wikidata | |

Estrogen (American English) or oestrogen (British English) is the primary female sex hormone as well as a medication. It is responsible for the development and regulation of the female reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics. Estrogen may also refer to any substance, natural or synthetic, that mimics the effects of the natural hormone.[1] The estrane steroid estradiol is the most potent and prevalent endogenous estrogen, although several metabolites of estradiol also have estrogenic hormonal activity. Estrogens are used as medications as part of some oral contraceptives, in hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal, hypogonadal, and transgender women, and in the treatment of certain hormone-sensitive cancers like prostate cancer and breast cancer. They are one of three types of sex hormones, the others being androgens/anabolic steroids like testosterone and progestogens like progesterone.

Estrogens are synthesized in all vertebrates[2] as well as some insects.[3] Their presence in both vertebrates and insects suggests that estrogenic sex hormones have an ancient evolutionary history. The three major naturally occurring forms of estrogen in women are estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3). Another type of estrogen called estetrol (E4) is produced only during pregnancy. Quantitatively, estrogens circulate at lower levels than androgens in both men and women.[4] While estrogen levels are significantly lower in males compared to females, estrogens nevertheless also have important physiological roles in males.[5]

Like all steroid hormones, estrogens readily diffuse across the cell membrane. Once inside the cell, they bind to and activate estrogen receptors (ERs) which in turn modulate the expression of many genes.[6] Additionally, estrogens bind to and activate rapid-signaling membrane estrogen receptors (mERs),[7][8] such as GPER (GPR30).[9]

Types and examples[edit]

Steroidal estrogens[edit]

Endogenous[edit]

The three major naturally occurring estrogens in women are estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3). Estradiol is the predominant estrogen during reproductive years both in terms of absolute serum levels as well as in terms of estrogenic activity. During menopause, estrone is the predominant circulating estrogen and during pregnancy estriol is the predominant circulating estrogen in terms of serum levels. Though estriol is the most plentiful of the three estrogens it is also the weakest, whereas estradiol is the strongest with a potency of approximately 80 times that of estriol.[10] Thus, estradiol is the most important estrogen in non-pregnant females who are between the menarche and menopause stages of life. However, during pregnancy this role shifts to estriol, and in postmenopausal women estrone becomes the primary form of estrogen in the body. Another type of estrogen called estetrol (E4) is produced only during pregnancy. All of the different forms of estrogen are synthesized from androgens, specifically testosterone and androstenedione, by the enzyme aromatase.

Other endogenous estrogens, the biosyntheses of which do not involve aromatase, include 27-hydroxycholesterol, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), 7-oxo-DHEA, 7α-hydroxy-DHEA, 16α-hydroxy-DHEA, 7β-hydroxyepiandrosterone, 4-androstenedione, 5-androstenediol, 3α-androstanediol, and 3β-androstanediol, and may have important endogenous functions as estrogens.[11][12] Some estrogen metabolites, such as the catechol estrogens 2-hydroxyestradiol, 2-hydroxyestrone, 4-hydroxyestradiol, and 4-hydroxyestrone, as well as 16α-hydroxyestrone, are also estrogens with varying degrees of activity.[13]

Pharmaceuticals[edit]

Estradiol, estrone, and estriol have all been approved as pharmaceutical drugs and are used medically. Estetrol is currently under development for medical indications, but has not yet been approved in any country.[14] A variety of synthetic estrogen esters, such as estradiol valerate, estradiol cypionate, estradiol acetate, estradiol undecylate, polyestradiol phosphate, and estradiol benzoate, are used clinically. The aforementioned compounds behave as prodrugs to estradiol, and are longer-lasting in comparison. Esters of estrone and estriol also exist and are employed in clinical medicine.

Ethinylestradiol (EE) is a more potent synthetic analogue of estradiol that is used widely in hormonal contraceptives. Mestranol, moxestrol, and quinestrol are derivatives of EE used clinically. A related drug is methylestradiol, which is also used clinically. Conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs), such as Premarin, a commonly prescribed estrogenic drug produced from the urine of pregnant mares, include the natural steroidal estrogens equilin and equilenin, as well as, especially, estrone sulfate (which itself is inactive and becomes active upon conversion into estrone). A related and very similar product to CEEs is esterified estrogens (EEs).

Testosterone, which is available as a pharmaceutical drug, is metabolized in part to estrogens such as estradiol, and can produce significant estrogenic effects at high dosages, most notably gynecomastia in males. The same is true for some synthetic anabolic-androgenic steroids, like methyltestosterone and metandienone. DHEA is available over-the-counter as a dietary supplement in the United States (but not in many other countries), though it is only very weakly estrogenic.

Non-steroidal estrogens[edit]

Pharmaceuticals[edit]

Diethylstilbestrol is a non-steroidal estrogen that is no longer used medically. It is a member of the stilbestrol group. Other stilbestrol estrogens that have been used clinically include benzestrol, dienestrol, dienestrol acetate, diethylstilbestrol dipropionate, fosfestrol, hexestrol, and methestrol dipropionate. Chlorotrianisene, methallenestril, and doisynoestrol are non-steroidal estrogens structurally distinct from the stilbestrols that have also been used clinically.

Xenoestrogens[edit]

A range of synthetic and natural substances that possess estrogenic activity have been identified in the environment and are referred to xenoestrogens.[15]

- Synthetic substances such as bisphenol A as well as metalloestrogens (e.g., cadmium).

- Plant products with estrogenic activity are called phytoestrogens (e.g., coumestrol, daidzein, genistein, miroestrol).

- Those produced by fungi are known as mycoestrogens (e.g., zearalenone).

Biological function[edit]

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The actions of estrogen are mediated by the estrogen receptor (ER), a dimeric nuclear protein that binds to DNA and controls gene expression. Like other steroid hormones, estrogen enters passively into the cell where it binds to and activates the estrogen receptor. The estrogen:ER complex binds to specific DNA sequences called a hormone response element to activate the transcription of target genes (in a study using an estrogen-dependent breast cancer cell line as model, 89 such genes were identified).[17] Since estrogen enters all cells, its actions are dependent on the presence of the ER in the cell. The ER is expressed in specific tissues including the ovary, uterus and breast. The metabolic effects of estrogen in postmenopausal women has been linked to the genetic polymorphism of the ER.[18]

While estrogens are present in both men and women, they are usually present at significantly higher levels in women of reproductive age. They promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts, and are also involved in the thickening of the endometrium and other aspects of regulating the menstrual cycle. In males, estrogen regulates certain functions of the reproductive system important to the maturation of sperm[19][20][21] and may be necessary for a healthy libido.[22] Furthermore, there are several other structural changes induced by estrogen in addition to other functions.

Overview of actions[edit]

| This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Structural

- Mediate formation of female secondary sex characteristics

- Accelerate metabolism

- Increase fat store

- Stimulate endometrial growth

- Increase uterine growth

- Increase vaginal lubrication

- Thicken the vaginal wall

- Maintenance of vessel and skin

- Reduce bone resorption, increase bone formation

- Protein synthesis

- Increase hepatic production of binding proteins

- Coagulation

- Increase circulating level of factors 2, 7, 9, 10, plasminogen

- Decrease antithrombin III

- Increase platelet adhesiveness

- Lipid

- Increase HDL, triglyceride

- Decrease LDL, fat deposition

- Fluid balance

- Gastrointestinal tract

- Reduce bowel motility

- Increase cholesterol in bile

- Melanin

- Increase pheomelanin, reduce eumelanin

- Cancer

- Support hormone-sensitive breast cancers (see section below)

- Lung function

- Uterus lining

- Estrogen together with progesterone promotes and maintains the uterus lining in preparation for implantation of fertilized egg and maintenance of uterus function during gestation period, also upregulates oxytocin receptor in myometrium

- Ovulation

- Surge in estrogen level induces the release of luteinizing hormone, which then triggers ovulation by releasing the egg from the Graafian follicle in the ovary.

- Sexual behavior

- Promotes sexual receptivity in estrus,[24] and induces lordosis behavior.[25] In non-human mammals, it also induces estrus (in heat) prior to ovulation, which also induces lordosis behavior. Female non-human mammals are not sexually receptive without the estrogen surge, i.e., they have no mating desire when not in estrus.

- Regulates the stereotypical sexual receptivity behavior; this lordosis behavior is estrogen-dependent, which is regulated by the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus.[26]

- Sex drive is dependent on androgen levels[27] only in the presence of estrogen, but without estrogen, free testosterone level actually decreases sexual desire (instead of increases sex drive), as demonstrated for those women who have hypoactive sexual desire disorder, and the sexual desire in these women can be restored by administration of estrogen (using oral contraceptive).[28] In non-human mammals, mating desire is triggered by estrogen surge in estrus.

Female pubertal development[edit]

Estrogens are responsible for the development of female secondary sexual characteristics during puberty, including breast development, widening of the hips, and female fat distribution. Conversely, androgens are responsible for pubic and body hair growth, as well as acne and axillary odor.

Breast development[edit]

Estrogen, in conjunction with growth hormone (GH) and its secretory product insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), is critical in mediating breast development during puberty, as well as breast maturation during pregnancy in preparation of lactation and breastfeeding.[29][30] Estrogen is primarily and directly responsible for inducing the ductal component of breast development,[31][32][33] as well as for causing fat deposition and connective tissue growth.[31][32] It is also indirectly involved in the lobuloalveolar component, by increasing progesterone receptor expression in the breasts[31][33][34] and by inducing the secretion of prolactin.[35][36] Allowed for by estrogen, progesterone and prolactin work together to complete lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy.[32][37]

Androgens such as testosterone powerfully oppose estrogen action in the breasts, such as by reducing estrogen receptor expression in them.[38][39]

Female reproductive system[edit]

Estrogens are responsible for maturation and maintenance of the vagina and uterus, and are also involved in ovarian function, such as maturation of ovarian follicles. In addition, estrogens play an important role in regulation of gonadotropin secretion. For these reasons, estrogens are required for female fertility.

Brain and behavior[edit]

Sex drive[edit]

Estrogens are involved in sex drive in both women and men.

Cognition[edit]

Verbal memory scores are frequently used as one measure of higher level cognition. These scores vary in direct proportion to estrogen levels throughout the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause. Furthermore, estrogens when administered shortly after natural or surgical menopause prevents decreases in verbal memory. In contrast, estrogens have little effect on verbal memory if first administered years after menopause.[40] Estrogens also have positive influences on other measures of cognitive function.[41] However the effect of estrogens on cognition is not uniformly favorable and is dependent on the timing of the dose and the type of cognitive skill being measured.[42]

The protective effects of estrogens on cognition may be mediated by estrogens anti-inflammatory effects in the brain.[43] Studies have also shown that the Met allele gene and level of estrogen mediates the efficiency of prefrontal cortex dependent working memory tasks.[44][45]

Mental health[edit]

Estrogen is considered to play a significant role in women’s mental health. Sudden estrogen withdrawal, fluctuating estrogen, and periods of sustained estrogen low levels correlate with significant mood lowering. Clinical recovery from postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause depression has been shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized and/or restored.[46][47][48]

Compulsions in male lab mice, such as those in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), may be caused by low estrogen levels. When estrogen levels were raised through the increased activity of the enzyme aromatase in male lab mice, OCD rituals were dramatically decreased. Hypothalamic protein levels in the gene COMT are enhanced by increasing estrogen levels which are believed to return mice that displayed OCD rituals to normal activity. Aromatase deficiency is ultimately suspected which is involved in the synthesis of estrogen in humans and has therapeutic implications in humans having obsessive-compulsive disorder.[49]

Local application of estrogen in the rat hippocampus has been shown to inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin. Contrarily, local application of estrogen has been shown to block the ability of fluvoxamine to slow serotonin clearance, suggesting that the same pathways which are involved in SSRI efficacy may also be affected by components of local estrogen signaling pathways.[50]

Parenthood[edit]

Studies have also found that fathers had lower levels of cortisol and testosterone but higher levels of estrogen (estradiol) compared to non-fathers.[51]

Binge eating[edit]

Estrogen may play a role in suppressing binge eating. Hormone replacement therapy using estrogen may be a possible treatment for binge eating behaviors in females. Estrogen replacement has been shown to suppress binge eating behaviors in female mice.[52] The mechanism by which estrogen replacement inhibits binge-like eating involves the replacement of serotonin (5-HT) neurons. Women exhibiting binge eating behaviors are found to have increased brain uptake of neuron 5-HT, and therefore less of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the cerebrospinal fluid.[53] Estrogen works to activate 5-HT neurons, leading to suppression of binge like eating behaviors.[52]

It is also suggested that there is an interaction between hormone levels and eating at different points in the female menstrual cycle. Research has predicted increased emotional eating during hormonal flux, which is characterized by high progesterone and estradiol levels that occur during the mid-luteal phase. It is hypothesized that these changes occur due to brain changes across the menstrual cycle that are likely a genomic effect of hormones. These effects produce menstrual cycle changes, which result in hormone release leading to behavioral changes, notably binge and emotional eating. These occur especially prominently among women who are genetically vulnerable to binge eating phenotypes.[54]

Binge eating is associated with decreased estradiol and increased progesterone.[55] Klump et al.[56] Progesterone may moderate the effects of low estradiol (such as during dysregulated eating behavior), but that this may only be true in women who have had clinically diagnosed binge episodes (BEs). Dysregulated eating is more strongly associated with such ovarian hormones in women with BEs than in women without BEs.[56]

The implantation of 17β-estradiol pellets in ovariectomized mice significantly reduced binge eating behaviors and injections of GLP-1 in ovariectomized mice decreased binge-eating behaviors.[52]

The associations between binge eating, menstrual-cycle phase and ovarian hormones correlated.[55][57][57][58]

Masculinization in rodents[edit]

In rodents, estrogens (which are locally aromatized from androgens in the brain) play an important role in psychosexual differentiation, for example, by masculinizing territorial behavior;[59] the same is not true in humans.[60] In humans, the masculinizing effects of prenatal androgens on behavior (and other tissues, with the possible exception of effects on bone) appear to act exclusively through the androgen receptor.[61] Consequently, the utility of rodent models for studying human psychosexual differentiation has been questioned.[62]

Bone/skeletal system[edit]

Estrogens are responsible for both the pubertal growth spurt, which causes an acceleration in linear growth, and epiphyseal closure, which limits height and limb length, in both females and males. In addition, estrogens are responsible for bone maturation and maintenance of bone mineral density throughout life. Due to hypoestrogenism, the risk of osteoporosis increases during menopause.

Cardiovascular system[edit]

Women suffer less from heart disease due to vasculo-protective action of estrogen which helps in preventing atherosclerosis.[63] It also helps in maintaining the delicate balance between fighting infections and protecting arteries from damage thus lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease.[64]

Immune system[edit]

Estrogen has anti-inflammatory properties and helps in mobilization of polymorphonuclear white blood cells or neutrophils.[64]

Associated conditions[edit]

Estrogens are implicated in various estrogen-dependent conditions, such as ER-positive breast cancer, as well as a number of genetic conditions involving estrogen signaling or metabolism, such as estrogen insensitivity syndrome, aromatase deficiency, and aromatase excess syndrome.

Biochemistry[edit]

Biosynthesis[edit]

Estrogens, in females, are produced primarily by the ovaries, and during pregnancy, the placenta.[66] Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates the ovarian production of estrogens by the granulosa cells of the ovarian follicles and corpora lutea. Some estrogens are also produced in smaller amounts by other tissues such as the liver, adrenal glands, and the breasts. These secondary sources of estrogens are especially important in postmenopausal women. Fat cells produce estrogen as well.[67]

In females, synthesis of estrogens starts in theca interna cells in the ovary, by the synthesis of androstenedione from cholesterol. Androstenedione is a substance of weak androgenic activity which serves predominantly as a precursor for more potent androgens such as testosterone as well as estrogen. This compound crosses the basal membraneinto the surrounding granulosa cells, where it is converted either immediately into estrone, or into testosterone and then estradiol in an additional step. The conversion of androstenedione to testosterone is catalyzed by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD), whereas the conversion of androstenedione and testosterone into estrone and estradiol, respectively is catalyzed by aromatase, enzymes which are both expressed in granulosa cells. In contrast, granulosa cells lack 17α-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase, whereas theca cells express these enzymes and 17β-HSD but lack aromatase. Hence, both granulosa and theca cells are essential for the production of estrogen in the ovaries.

Estrogen levels vary through the menstrual cycle, with levels highest near the end of the follicular phase just before ovulation.

Metabolism[edit]

Estrogens are metabolized via hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP1A1 and CYP3A4 and via conjugation by estrogen sulfotransferases (sulfation) and UDP-glucuronyltransferases (glucuronidation). In addition, estradiol is dehydrogenated by 17β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase into the much less potent estrogen estrone. These reactions occur primarily in the liver, but also in other tissues.

Medical uses[edit]

Hormonal contraception[edit]

Since estrogen circulating in the blood can negatively feedback to reduce circulating levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), most oral contraceptives contain ethinylestradiol, along with a progestin (synthetic progestogen). Even in men, the major hormone involved in LH feedback is estradiol, not testosterone.[68][69]

Hormone replacement therapy[edit]

Estrogen and other hormones are given to postmenopausal women in order to prevent osteoporosis as well as treat the symptoms of menopause such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, urinary stress incontinence, chilly sensations, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, and sweating. Fractures of the spine, wrist, and hips decrease by 50–70% and spinal bone density increases by ~5% in those women treated with estrogen within 3 years of the onset of menopause and for 5–10 years thereafter.

Before the specific dangers of conjugated equine estrogens were well understood, standard therapy was 0.625 mg/day of conjugated equine estrogens (such as Premarin). There are, however, risks associated with conjugated equine estrogen therapy. Among the older postmenopausal women studied as part of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), an orally administered conjugated equine estrogen supplement was found to be associated with an increased risk of dangerous blood clotting. The WHI studies used one type of estrogen supplement, a high oral dose of conjugated equine estrogens (Premarin alone and with medroxyprogesterone acetate as PremPro).[70]

In a study by the NIH, esterified estrogens were not proven to pose the same risks to health as conjugated equine estrogens. Hormone replacement therapy has favorable effects on serum cholesterol levels, and when initiated immediately upon menopause may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease, although this hypothesis has yet to be tested in randomized trials. Estrogen appears to have a protector effect on atherosclerosis: it lowers LDL and triglycerides, it raises HDL levels and has endothelial vasodilatation properties plus an anti-inflammatory component.

Research is underway to determine if risks of estrogen supplement use are the same for all methods of delivery. In particular, estrogen applied topically may have a different spectrum of side-effects than when administered orally,[71] and transdermal estrogens do not affect clotting as they are absorbed directly into the systemic circulation, avoiding first-pass metabolism in the liver. This route of administration is thus preferred in women with a history of thrombo-embolic disease.

Estrogen is also used in the therapy of vaginal atrophy, hypoestrogenism (as a result of hypogonadism, oophorectomy, or primary ovarian failure), amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, and oligomenorrhea. Estrogens can also be used to suppress lactation after child birth.

Prostate cancer[edit]

High dose estrogen therapy with estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol, ethinylestradiol, and estradiol undecylate has been used in the past to treat prostate cancer in men.[72] It is effective because estrogens are functional antiandrogens, capable of suppressing testosterone levels to castrate concentrations and decreasing free testosterone levels by increasing sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) production. High dose estrogen therapy is associated with poor tolerability and safety, namely severe gynecomastia and cardiovascular complications such as thrombosis, and for this reason, has largely been replaced by newer antiandrogens such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and non-steroidal antiandrogens. It is still sometimes used in the treatment of prostate cancer however,[72] and newer estrogens with atypical profiles such as GTx-758 that have improved tolerability profiles are being studied for possible application in prostate cancer.

Breast cancer[edit]

High doses of potent estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol were used in the past in the treatment of breast cancer.[73] Their effectiveness is approximately equivalent to that of antiestrogen therapy with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors.[73] The use of high dose estrogen therapy in breast cancer has mostly been superseded by antiestrogen therapy due to the improved safety profile of the latter.[73]

About 80% of breast cancers, once established, rely on supplies of the hormone estrogen to grow: they are known as hormone-sensitive or hormone-receptor-positive cancers. Prevention of the actions or production of estrogen in the body is a treatment for these cancers.

Hormone-receptor-positive breast cancers are treated with drugs which suppress production or interfere with the action of estrogen in the body.[74] This technique, in the context of treatment of breast cancer, is known variously as hormonal therapy, hormone therapy, or anti-estrogen therapy (not to be confused with hormone replacement therapy). Certain foods such as soy may also suppress the proliferative effects of estrogen and are used as an alternative to hormone therapy.[75]

Others[edit]

Tall stature[edit]

Estrogen has been used to induce growth attenuation in tall girls.[76]

Estrogen-induced growth attenuation was used as part of the controversial Ashley Treatment to keep a developmentally disabled girl from growing to adult size.[77]

Bulimia[edit]

Most recently, estrogen has been used in experimental research as a way to treat women suffering from bulimia nervosa, in addition to cognitive behavioral therapy, which is the established standard for treatment in bulimia cases. The estrogen research hypothesizes that the disease may be linked to a hormonal imbalance in the brain.[78]

Miscellaneous[edit]

Estrogen has also been used in studies which indicate that it may be an effective drug for use in the treatment of traumatic liver injury.[79]

In humans and mice, estrogen promotes wound healing.[80]

Adverse effects[edit]

Hyperestrogenism (elevated levels of estrogen) may be a result of exogenous administration of estrogen or estrogen-like substances, or may be a result of physiologic conditions such as pregnancy. Any of these causes is linked with an increase in the risk of thrombosis.[81] It's also a symptom of liver cirrhosis, due to lowered metabolic function of the liver, which metabolises estrogen, leading to spider angioma, palmary erythema, gynecomastia and testicular atrophy in some male patients.

The estrogen-alone substudy of the WHI reported an increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in postmenopausal women 50 years of age or older and an increased risk of dementia in postmenopausal women 65 years of age or older using 0.625 mg of Premarin conjugated equine estrogens (CEE). The estrogen-plus-progestin substudy of the WHI reported an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, invasive breast cancer, pulmonary emboli and DVT in postmenopausal women 50 years of age or older and an increased risk of dementia in postmenopausal women 65 years of age or older using PremPro, which is 0.625 mg of CEE with 2.5 mg of the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA).[82][83][84]

The labeling of estrogen-only products in the U.S. includes a boxed warning that unopposed estrogen (without progestogen) therapy increases the risk of endometrial cancer. Based on a review of data from the WHI, in 2003 the FDA changed the labeling of all estrogen and estrogen with progestin products for use by postmenopausal women to include a new boxed warning about cardiovascular and other risks.

Cosmetics[edit]

Some hair shampoos on the market include estrogens and placental extracts; others contain phytoestrogens. In 1998, there were case reports of four prepubescent African-American girls developing breasts after exposure to these shampoos.[85] In 1993, the FDA determined that not all over-the-counter topically applied hormone-containing drug products for human use are generally recognized as safe and effective and are misbranded. An accompanying proposed rule deals with cosmetics, concluding that any use of natural estrogens in a cosmetic product makes the product an unapproved new drug and that any cosmetic using the term "hormone" in the text of its labeling or in its ingredient statement makes an implied drug claim, subjecting such a product to regulatory action.[86]

In addition to being considered misbranded drugs, products claiming to contain placental extract may also be deemed to be misbranded cosmetics if the extract has been prepared from placentas from which the hormones and other biologically active substances have been removed and the extracted substance consists principally of protein. The FDA recommends that this substance be identified by a name other than "placental extract" and describing its composition more accurately because consumers associate the name "placental extract" with a therapeutic use of some biological activity.[86]

History[edit]

In 1929, Adolf Butenandt and Edward Adelbert Doisy independently isolated and purified estrone, the first estrogen to be discovered.[87] Thereafter, the pace of hormonal drug research accelerated. The "first orally effective estrogen", Emmenin, derived from the late-pregnancy urine of Canadian women, was introduced in 1930 by Collip and Ayerst Laboratories. Estrogens have poor oral bioavailability and prior to the development of micronization could not be given orally, but the urine was found to contain estriol glucuronide, which is absorbed orally and becomes active in the body after hydrolysis. Scientists continued to search for new sources of estrogen because of concerns associated with the practicality of introducing the drug into the market. At the same time, a German pharmaceutical drug company, Schering, formulated a similar product as Emmenin called Progynon that was introduced to German women to treat menopausal symptoms.

In 1938, British scientists obtained a patent on a newly formulated nonsteroidal estrogen, diethylstilbestrol (DES), that was cheaper and more powerful than the previously manufactured estrogens. Soon after, concerns over the side effects of DES were raised in scientific journals while the drug manufacturers came together to lobby for governmental approval of DES. It was only until 1941 when estrogen therapy was finally approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[88] Premarin (conjugated equine estrogens) was introduced in 1941 and succeeded Emmenin, the sales of which had begun to drop after 1940 due to competition from DES.[89] Ethinylestradiol was synthesized in 1938 by Hans Herloff Inhoffen and Walter Hohlweg at Schering AG in Berlin[90][91][92][93][94] and was approved by the FDA in the U.S. on June 25, 1943 and marketed by Schering as Estinyl.[95]

Micronized estradiol, via the oral route, was first evaluated in 1972,[96] and this was followed by the evaluation of vaginal and intranasal micronized estradiol in 1977.[97]Oral micronized estradiol was first approved in the United States under the brand name Estrace in 1975.[98]

Society and culture[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The name estrogen is derived from the Greek οἶστρος (oistros), literally meaning "verve or inspiration" but figuratively sexual passion or desire,[99] and the suffix -gen, meaning "producer of".

Environmental effects[edit]

Estrogens are among the wide range of endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs) because they have high estrogenic potency. When an EDC makes its way into the environment, it may cause male reproductive dysfunction to wildlife.[100] The estrogen excreted from farm animals makes its way into fresh water systems.[101] During the germination period of reproduction the fish are exposed to low levels of estrogen which may cause reproductive dysfunction to male fish.[102][103]