Glycyrrhizin induces apoptosis in human stomach cancer KATO III a

Glycyrrhizin kháng KATOIII

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Epigen, Glycyron |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic and by intestinal bacteria |

| Biological half-life | 6.2-10.2 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Faeces, urine (0.31-0.67%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| E number | E958 (glazing agents, ...) |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.350 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

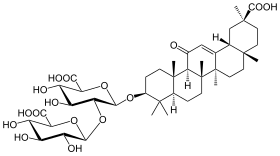

| Formula | C42H62O16 |

| Molar mass | 822.93 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | |

| Solubility in water | 1-10 mg/mL (20 °C) |

Glycyrrhizin (or glycyrrhizic acid or glycyrrhizinic acid) is the chief sweet-tasting constituent of Glycyrrhiza glabra(liquorice) root. Structurally it is a saponin and has been used as an emulsifier and gel-forming agent in foodstuff and cosmetics. Its aglycone is enoxolone and it has therefore been used as a prodrug for that compound, for example it is used in Japan to prevent liver carcinogenesis in patients with chronic hepatitis C.[3]

Contents

[hide]Medical uses[edit]

Glycyrrhizin inhibits liver cell injury and is given intravenously for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis and cirrhosis in Japan.[4][5] In one small scale preliminary clinical trial, it was found that early treatment with glycyrrhizin might prevent disease progression in patients with acute onset autoimmune hepatitis.[6]

Adverse effects[edit]

The most widely reported side effects of glycyrrhizin use are fluid retention. These effects are related to the inhibition of cortisol metabolism within the kidney, and the subsequent stimulation of the mineralocorticoid receptors.[7] Other side effects include:[8]

- Headache

- Paralysis

- Transient visual loss

- Torsades de pointes

- Tachycardia

- Cardiac arrest

- Hypokalaemia

- Reduced testosterone

- Premature birth

- Acute kidney failure

- Muscle weakness

- Myopathy

- Myoglobinuria

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Increased body weight

Mechanism of action[edit]

It inhibits the enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, which likely contributes to its anti-inflammatory and mineralocorticoid activity.[8] It has a broad-spectrum of antiviral activity in vitro against:[8][9]

- Herpes simplex virus,[10] which has also been confirmed in vivo.[11]

- Influenzavirus (including H5N1)[12]

- Varicella zoster virus[13]

- SARS coronavirus

- HIV

- Hepatitis A virus

- Hepatitis B virus

- Hepatitis C virus

- Hepatitis E virus

- Epstein–Barr virus

- Human cytomegalovirus

- Flavivirus

- Japanese encephalitis virus

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

After oral ingestion, glycyrrhizin is first hydrolysed to 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid by intestinal bacteria. After complete absorption from the gut, β-glycyrrhetinic acid is metabolised to 3β-monoglucuronyl-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid in the liver. This metabolite then circulates in the bloodstream. Consequently, its oral bioavailability is poor. The main part is eliminated by bile and only a minor part (0.31–0.67%) by urine.[14] After oral ingestion of 600 mg of glycyrrhizin the metabolite appeared in urine after 1.5 to 14 hours. Maximal concentrations (0.49 to 2.69 mg/l) were achieved after 1.5 to 39 hours and metabolite can be detected in the urine after 2 to 4 days.[14]