Changes in Levels of Expression of p53 and the Product of the bcl-2 in

Cisplatin kháng KATOIII

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Platinol, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684036 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 100% (IV) |

| Protein binding | > 95% |

| Biological half-life | 30–100 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| Synonyms | cisplatinum, platamin, neoplatin, cismaplat, cis-diamminedichloridoplatinum(II) (CDDP) |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.106 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

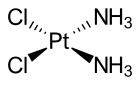

| Formula | [Pt(NH3)2Cl2] |

| Molar mass | 300.01 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | |

| | |

Cisplatin is a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of cancers. This includes testicular cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, breast cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancer, esophageal cancer, lung cancer, mesothelioma, brain tumors and neuroblastoma. It is used by injection into a vein.[1]

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, hearing problems, kidney problems, and vomiting. Other serious side effects include numbness, trouble walking, allergic reactions, electrolyte problems, and heart disease. Use during pregnancy is known to harm the baby. Cisplatin is in the platinum-based antineoplastic family of medications. It works in part by binding to and blocking the duplication of DNA.[1]

Cisplatin was discovered in 1845 and licensed for medical use in 1978/1979.[2][1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[3] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about 5.56 to 7.98 USD per 50 mg vial.[4] In the United Kingdom this costs the NHS about £17.[5]

Contents

[hide]Medical use[edit]

Cisplatin is administered intravenously as short-term infusion in normal saline for treatment of solid malignancies. It is used to treat various types of cancers, including sarcomas, some carcinomas (e.g., small cell lung cancer, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and ovarian cancer), lymphomas, bladder cancer, cervical cancer,[6] and germ cell tumors.

Cisplatin is particularly effective against testicular cancer; the cure rate was improved from 10% to 85%.[7]

In addition, cisplatin is used in Auger therapy.

Side effects[edit]

Cisplatin has a number of side-effects that can limit its use:

- Nephrotoxicity (kidney damage) is a major concern. The dose is reduced when the patient's creatinine clearance (a measure of renal function) is reduced. Adequate hydration and diuresis is used to prevent renal damage. The nephrotoxicity of platinum-class drugs seems to be related to reactive oxygen species and in animal models can be ameliorated by free radical scavenging agents (e.g., amifostine). Nephrotoxicity is a dose-limiting side effect.[8]

- Neurotoxicity (nerve damage) can be anticipated by performing nerve conduction studies before and after treatment. Common neurological side effects of cisplatin include visual perception and hearing disorder, which can occur soon after treatment begins.[9] While triggering apoptosis through interfering with DNA replication remains the primary mechanism of cisplatin, this has not been found to contribute to neurological side effects. Recent studies have shown that cisplatin noncompetitively inhibits an archetypal, membrane-bound mechanosensitive sodium-hydrogen ion transporter known as NHE-1.[9] It is primarily found on cells of the peripheral nervous system, which are aggregated in large numbers near the ocular and aural stimuli-receiving centers. This noncompetitive interaction has been linked to hydroelectrolytic imbalances and cytoskeleton alterations, both of which have been confirmed in vitro and in vivo. However, NHE-1 inhibition has been found to be both dose-dependent (half-inhibition = 30 µg/mL) and reversible.[9]

- Nausea and vomiting: cisplatin is one of the most emetogenic chemotherapy agents, but this symptom is managed with prophylactic antiemetics (ondansetron, granisetron, etc.) in combination with corticosteroids. Aprepitant combined with ondansetron and dexamethasone has been shown to be better for highly emetogenic chemotherapy than just ondansetron and dexamethasone.

- Ototoxicity (hearing loss): there is at present no effective treatment to prevent this side effect, which may be severe. Audiometric analysis may be necessary to assess the severity of ototoxicity. Other drugs (such as the aminoglycoside antibiotic class) may also cause ototoxicity, and the administration of this class of antibiotics in patients receiving cisplatin is generally avoided. The ototoxicity of both the aminoglycosides and cisplatin may be related to their ability to bind to melanin in the stria vascularis of the inner ear or the generation of reactive oxygen species.

- Electrolyte disturbance: Cisplatin can cause hypomagnesaemia, hypokalaemia and hypocalcaemia. The hypocalcaemia seems to occur in those with low serum magnesium secondary to cisplatin, so it is not primarily due to the cisplatin.

- Hemolytic anemia can be developed after several courses of cisplatin. It is suggested that an antibody reacting with a cisplatin-red-cell membrane is responsible for hemolysis.[10]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Cisplatin interferes with DNA replication, which kills the fastest proliferating cells, which in theory are carcinogenic. Following administration, one of the two chloride ligands is slowly displaced by water to give the aquo complex cis-[PtCl(NH3)2(H2O)]+, in a process termed aquation. Dissociation of the chloride ligand is favored inside the cell because the intracellular chloride concentration is only 3–20% of the approximately 100 mM chloride concentration in the extracellular fluid.[11][12]

The aqua ligand in cis-[PtCl(NH3)2(H2O)]+ is itself easily displaced by the N-heterocyclic bases on DNA. Guanine preferentially binds. Subsequent to formation of [PtCl(guanine-DNA)(NH3)2]+, crosslinking can occur via displacement of the other chloride ligand, typically by another guanine.[13] Cisplatin crosslinks DNA in several different ways, interfering with cell division by mitosis. The damaged DNA elicits DNA repair mechanisms, which in turn activate apoptosis when repair proves impossible. In 2008, researchers were able to show that the apoptosis induced by cisplatin on human colon cancer cells depends on the mitochondrial serine-protease Omi/Htra2.[14] Since this was only demonstrated for colon carcinoma cells, it remains an open question if the Omi/Htra2 protein participates in the cisplatin-induced apoptosis in carcinomas from other tissues.

Most notable among the changes in DNA are the 1,2-intrastrand cross-links with purine bases. These include 1,2-intrastrand d(GpG) adducts which form nearly 90% of the adducts and the less common 1,2-intrastrand d(ApG) adducts. 1,3-intrastrand d(GpXpG) adducts occur but are readily excised by the nucleotide excision repair (NER). Other adducts include inter-strand crosslinks and nonfunctional adducts that have been postulated to contribute to cisplatin's activity. Interaction with cellular proteins, particularly HMG domain proteins, has also been advanced as a mechanism of interfering with mitosis, although this is probably not its primary method of action.

Although cisplatin is frequently designated as an alkylating agent, it has no alkyl group and it therefore cannot carry out alkylating reactions. It is correctly classified as alkylating-like.

Cisplatin resistance[edit]

Cisplatin combination chemotherapy is the cornerstone of treatment of many cancers. Initial platinum responsiveness is high but the majority of cancer patients will eventually relapse with cisplatin-resistant disease. Many mechanisms of cisplatin resistance have been proposed including changes in cellular uptake and efflux of the drug, increased detoxification of the drug, inhibition of apoptosis and increased DNA repair.[15] Oxaliplatin is active in highly cisplatin-resistant cancer cells in the laboratory; however, there is little evidence for its activity in the clinical treatment of patients with cisplatin-resistant cancer.[15] The drug paclitaxel may be useful in the treatment of cisplatin-resistant cancer; the mechanism for this activity is unknown.[16]

Transplatin[edit]

Transplatin, the trans stereoisomer of cisplatin, has formula trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2] and does not exhibit a comparably useful pharmacological effect. Its low activity is generally thought to be due to rapid deactivation of the drug before it can arrive at the DNA.[citation needed] It is toxic, and it is desirable to test batches of cisplatin for the absence of the trans isomer. In a procedure by Woollins et al., which is based on the classic Kurnakov test, thiourea reacts with the sample to give derivatives which can easily be separated and detected by HPLC.[17]

History[edit]

The compound cis-[Pt(NH3)2(Cl)2] was first described by Michele Peyrone in 1845, and known for a long time as Peyrone's salt.[18] The structure was deduced by Alfred Werner in 1893.[13] In 1965, Barnett Rosenberg, Van Camp et al. of Michigan State University discovered that electrolysis of platinum electrodes generated a soluble platinum complex which inhibited binary fission in Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. Although bacterial cell growth continued, cell division was arrested, the bacteria growing as filaments up to 300 times their normal length.[19] The octahedral Pt(IV) complex cis-[PtCl4(NH3)2], but not the trans isomer, was found to be effective at forcing filamentous growth of E. coli cells. The square planar Pt(II) complex, cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] turned out to be even more effective at forcing filamentous growth.[20][21] This finding led to the observation that cis-[PtCl2(NH3)2] was indeed highly effective at regressing the mass of sarcomas in rats.[22] Confirmation of this discovery, and extension of testing to other tumour cell lines launched the medicinal applications of cisplatin. Cisplatin was approved for use in testicular and ovarian cancers by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on 19 December 1978.,[13][23][24] and in the UK (and in several other European countries) in 1979.[25]

Synthesis[edit]

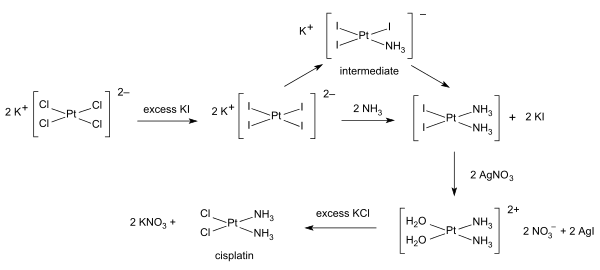

The synthesis of cisplatin starts from potassium tetrachloroplatinate.[26][27] The tetraiodide is formed by reaction with an excess of potassium iodide. Reaction with ammonia forms K2[PtI2(NH3)2] which is isolated as a yellow compound. When silver nitrate in water is added insoluble silver iodide precipitates and K2[Pt(OH2)2(NH3)2] remains in solution. Addition of potassium chloride will form the final product which precipitates [26] In the triiodo intermediate the addition of the second ammonia ligand is governed by the trans effect.[26]

For the synthesis of transplatin K2[PtCl4] is first converted to Cl2[Pt(NH3)4] by reaction with ammonia. The trans product is then formed by reaction with hydrochloric acid.[26]