Evidence for an interaction between proinsulin C-peptide and GPR146

C-peptide kháng KATOIII

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

| |

| ChemSpider | |

| MeSH | C-Peptide |

PubChem CID

| |

| Properties | |

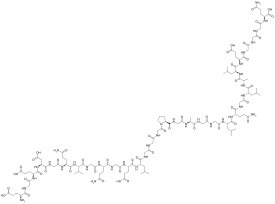

| C129H211N35O48 | |

| Molar mass | 3020.29 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Infobox references | |

The connecting peptide, or C-peptide, is a short 31-amino-acid polypeptide that connects insulin's A-chain to its B-chain in the proinsulin molecule. In diabetes and other diseases a measurement of C-peptide blood serum levels can be used to distinguish between certain diseases with similar clinical features.

In the insulin synthesis pathway, first preproinsulin is translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum of beta cells of the pancreas with an A-chain, a C-peptide, a B-chain, and a signal sequence. The signal sequence is cleaved from the N-terminus of the peptide by a signal peptidase, leaving proinsulin. After proinsulin is packaged into vesicles in the Golgi apparatus (beta-granules), the C-peptide is removed, leaving the A-chain B-chain, bound together by disulfide bonds, that constitute the insulin molecule.

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

Proinsulin C-peptide was first described in 1967 in connection with the discovery of the insulin biosynthesis pathway.[2] It serves as a linker between the A- and the B- chains of insulin and facilitates the efficient assembly, folding, and processing of insulin in the endoplasmic reticulum. Equimolar amounts of C-peptide and insulin are then stored in secretory granules of the pancreatic beta cells and both are eventually released to the portal circulation. Initially, the sole interest in C-peptide was as a marker of insulin secretion and has, as such, been of great value in furthering the understanding of the pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The first documented use of the C-peptide test was in 1972. During the past decade, however, C-peptide has been found to be a bioactive peptide in its own right, with effects on microvascular blood flow and tissue health.

Function[edit]

Cellular effects of C-peptide[edit]

C-peptide has been shown to bind to the surface of a number of cell types such as neuronal, endothelial, fibroblast and renal tubular, at nanomolar concentrations to a receptor that is likely G-protein-coupled. The signal activates Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling pathways such as MAPK, PLCγ, and PKC, leading to upregulation of a range of transcription factors as well as eNOS and Na+K+ATPase activities.[3] The latter two enzymes are known to have reduced activities in patients with type I diabetes and have been implicated in the development of long-term complications of type I diabetes such as peripheral and autonomic neuropathy.

In vivo studies in animal models of type 1 diabetes have established that C-peptide administration results in significant improvements in nerve and kidney function. Thus, in animals with early signs of diabetes-induced neuropathy, C peptide treatment in replacement dosage results in improved peripheral nerve function, as evidenced by increased nerve conduction velocity, increased nerve Na+,K+ ATPase activity, and significant amelioration of nerve structural changes.[4] Likewise, C-peptide administration in animals that had C-peptide deficiency (type 1 model) with nephropathy improves renal function and structure; it decreases urinary albumin excretion and prevents or decreases diabetes-induced glomerular changes secondary to mesangial matrix expansion.[5][6][7][8] C-peptide also has been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects as well as aid repair of smooth muscle cells.[9][10] ii

Clinical uses of C-peptide testing[edit]

- Patients with diabetes may have their C-peptide levels measured as a means of distinguishing type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes or Maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY).[11] Measuring C-peptide can help to determine how much of their own natural insulin a person is producing as C-peptide is secreted in equimolar amounts to insulin. C-peptide levels are measured instead of insulin levels because C-peptide can assess a person's own insulin secretion even if they receive insulin injections, and because the liver metabolizes a large and variable amount of insulin secreted into the portal vein but does not metabolise C-peptide, meaning blood C-peptide may be a better measure of portal insulin secretion than insulin itself.[12][13] A very low C-peptide confirms Type 1 diabetes and insulin dependence and is associated with high glucose variability, hyperglycaemia and increased complications. The test may be less helpful close to diagnosis, particularly where a patient is overweight and insulin resistant, as levels close to diagnosis in Type 1 diabetes may be high and overlap with those seen in type 2 diabetes.[14]

- Differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia. The test may be used to help determine the cause of hypoglycaemia (low glucose), values will be low if a person has taken an overdose of insulin but not suppressed if hypoglycaemia is due to an insulinoma or sulphonylureas.

- Factitious (or factitial) hypoglycemia may occur secondary to the surreptitious use of insulin. Measuring C-peptide levels will help differentiate a healthy patient from a diabetic one.

- C-peptide may be used for determining the possibility of gastrinomas associated with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasm syndromes (MEN 1). Since a significant number of gastrinomas are associated with MEN involving other hormone producing organs (pancreas, parathyroids, and pituitary), higher levels of C-peptide together with the presence of a gastrinoma suggest that organs besides the stomach may harbor neoplasms.

- C-peptide levels may be checked in women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) to help determine degree of insulin resistance.

Therapeutics[edit]

Therapeutic use of C-peptide has been explored in small clinical trials in diabetic kidney disease.[15][16] Creative Peptides,[17] Eli Lilly,[18] and Cebix[19] all had drug development programs for a C-peptide product. Cebix had the only ongoing program until it completed a Phase IIb trial in December 2014 that showed no difference between C-peptide and placebo, and it terminated its program and went out of business.[20][21]