Mackerel (Eicosapentaenoic acid) dược liệu kháng HL60

Mackerel is a common name applied to a number of different species of pelagic fish, mostly, but not exclusively, from the family Scombridae. They are found in both temperate and tropical seas, mostly living along the coast or offshore in the oceanic environment.

Mackerel typically have vertical stripes on their backs and deeply forked tails. Many species are restricted in their distribution ranges, and live in separate populations or fish stocks based on geography. Some stocks migrate in large schools along the coast to suitable spawning grounds, where they spawn in fairly shallow waters. After spawning they return the way they came, in smaller schools, to suitable feeding grounds often near an area of upwelling. From there they may move offshore into deeper waters and spend the winter in relative inactivity. Other stocks migrate across oceans.

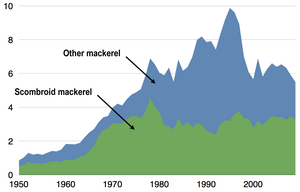

Smaller mackerel are forage fish for larger predators, including larger mackerel and Atlantic cod.[2] Flocks of seabirds, as well as whales, dolphins, sharks and schools of larger fish such as tuna and marlin follow mackerel schools and attack them in sophisticated and cooperative ways. Mackerel is high in omega-3 oils and is intensively harvested by humans. In 2009, over five million tons were landed by commercial fishermen[1] (see graph on the right). Sport fishermen value the fighting abilities of the king mackerel.[3]

Contents

[hide]Species[edit]

Over 30 different species, principally belonging to the family Scombridae, are commonly referred to as mackerel. The term "mackerel" means "marked" or "spotted", and derives from the Old French maquerel, around 1300, meaning a pimp or procurer. The connection is not altogether clear, but mackerel spawn enthusiastically in shoals near the coast, and medieval ideas on animal procreation were creative.[4]

Scombroid mackerels[edit]

About 21 species in the family Scombridae are commonly called mackerel. The type species for the scombroid mackerel is the Atlantic mackerel, Scomber scombrus. Until recently, Atlantic chub mackerel and Indo-Pacific chub mackerel were thought to be subspecies of the same species. In 1999, Collette established, on molecular and morphological considerations, that these are separate species.[5] Mackerel are smaller with shorter lifecycles than their close relatives, the tuna, which are also members of the same family.[6][7]

| This article is one of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| billfish, bonito mackerel, salmon shark, tuna |

| Forage |

| anchovy, herring menhaden, sardine shad, sprat |

| Demersal |

| cod, eel, flatfish pollock, ray |

| Mixed |

| carp, tilapia |

Scombrini, the true mackerels[edit]

The true mackerels belong to the tribe Scombrini.[8] The tribe consists of seven species, each belonging to one of two genera: Scomber and Rastrelliger.[9][10]

| [hide]True Mackerels (tribe Scombrini) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length | Common length | Maximum weight | Maximum age | Trophic level | FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

| Short mackerel | Rastrelliger brachysoma (Bleeker, 1851) | 34.5 cm | 20 cm | kg | years | 2.72 | [11] | [12] | |

| Island mackerel | R. faughni (Matsui, 1967) | 20 cm | cm | 0.75 kg | years | 3.4 | [14] | ||

| Indian mackerel | R. kanagurta (Cuvier, 1816) | 35 cm | 25 cm | kg | 4 years | 3.19 | [16] | [17] | |

| Blue mackerel | Scomber australasicus (Cuvier, 1832) | 44 cm | 30 cm | 1.36 kg | years | 4.2 | [19] | ||

| Atlantic chub mackerel | S. colias (Gmelin, 1789) | cm | cm | kg | years | 3.91 | [21] | ||

| Chub mackerel | S. japonicus (Houttuyn, 1782) | 64 cm | 30 cm | 2.9 kg | 18 years | 3.09 | [23] | [24] | |

| Atlantic mackerel | S. scombrus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 66 cm | cm | kg | 12 years west 18 years east | 3.65 | [26] | [27] | |

Scomberomorini, the Spanish mackerels[edit]

The Spanish mackerels belong to the tribe Scomberomorini, which is the "sister tribe" of the true mackerels.[28] This tribe consists of 21 species in all—18 of those are classified into the genus Scomberomorus,[29] two into Grammatorcynus,[30] and a single species into the monotypic genus Acanthocybium.[31]

| [hide]Spanish Mackerels (tribe Scomberomorini) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length | Common length | Maximum weight | Maximum age | Trophic level | FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

| Wahoo | Acanthocybium solandri (Cuvier in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1832) | 250 cm | 170 cm | 83 kg | years | 4.4 | [32] | ||

| Shark mackerel | Grammatorcynus bicarinatus (Quoy & Gaimard, 1825) | 112 cm | cm | 13.5 kg | years | 4.5 | [34] | ||

| Double-lined mackerel | G. bilineatus (Rüppell, 1836) | 100 cm | 50 cm | 3.5 kg | years | 4.18 | [36] | ||

| Serra Spanish mackerel | Scomberomorus brasiliensis (Collette, Russo & Zavala-Camin, 1978) | cm | cm | kg | years | 3.31 | [38] | ||

| King mackerel | S. cavalla (Cuvier, 1829) | 184 cm | 70 cm | 45 kg | 14 years | 4.5 | [40] | [41] | |

| Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel | S. commerson (Lacepède, 1800) | 240 cm | 120 cm | kg | years | 4.5 | [43] | [44] | |

| Monterey Spanish mackerel | S. concolor (Lockington, 1879) | cm | cm | kg | years | 4.24 | [46] | ||

| Indo-Pacific king mackerel | S. guttatus (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) | 76 cm | 55 cm | kg | years | 4.28 | [48] | [49] | |

| Korean mackerel | S. koreanus (Kishinouye, 1915) | 150 cm | 60 cm | 15 kg | years | 4.2 | [51] | ||

| Streaked Spanish mackerel | S. lineolatus (Cuvier, 1829) | 80 cm | 70 cm | kg | years | 4.5 | [53] | ||

| Atlantic Spanish mackerel | S. maculatus (Mitchill, 1815) | 91 cm | cm | 5.89 kg | 5 years | 4.5 | [55] | [56] | |

| Papuan Spanish mackerel | S. multiradiatus Munro, 1964 | 35 cm | cm | 0.5 kg | years | 4.0 | [58] | ||

| Australian spotted mackerel | S. munroi (Collette & Russo, 1980) | 104 cm | cm | 10.2 kg | years | 4.3 | [60] | ||

| Japanese Spanish mackerel | S. niphonius (Cuvier, 1832) | 100 cm | cm | 7.1 kg | years | 4.5 | [62] | [63] | |

| Queen mackerel | S. plurilineatus Fourmanoir, 1966 | 120 cm | cm | 12.5 kg | years | 4.2 | [65] | ||

| Queensland school mackerel | S. queenslandicus (Munro, 1943) | 100 cm | 80 cm | 12.2 kg | years | 4.5 | [67] | ||

| Cero mackerel | S. regalis (Bloch, 1793) | 183 cm | cm | 7.8 kg | years | 4.5 | [69] | ||

| Broadbarred king mackerel | S. semifasciatus (Macleay, 1883) | 120 cm | cm | kg | 10 years | 4.5 | [71] | ||

| Pacific sierra | S. sierra (Cuvier, 1832) | 99 cm | 60 cm | 8.2 kg | years | 4.5 | [73] | ||

| Chinese mackerel | S. sinensis (Cuvier, 1832) | 247 cm | 100 cm | kg | years | 4.5 | [75] | ||

| West African Spanish mackerel | S. tritor (Cuvier, 1832) | cm | cm | kg | years | 4.26 | [77] | ||

Other mackerel[edit]

In addition, a number of species with mackerel-like characteristics in the families Carangidae, Hexagrammidae and Gempylidae are commonly referred to as mackerel. There has been some confusion between the Pacific jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus) and the heavily harvested Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi). These have been thought at times to be the same species, but are now recognised as separate species.[79]

| [hide]Other mackerel species | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length | Common length | Maximum weight | Maximum age | Trophic level | FishBase | FAO | IUCN status |

| Scombridae Gasterochisma | Butterfly mackerel | Gasterochisma melampusRichardson, 1845 | 175 cm | 153 cm | kg | years | 4.4 | [80] | ||

| Carangidae Jack mackerel | Atlantic horse mackerel | Trachurus trachurus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 70 cm | 22 cm | 2.0 kg | years | 3.64 | [82] | [83] | Not assessed |

| Blue jack mackerel | T. picturatus (Bowdich, 1825) | 60 cm | 25 cm | kg | years | 3.32 | [84] | |||

| Cape horse mackerel | T. capensis (Castelnau, 1861) | 60 cm | 30 cm | kg | years | 3.47 | [86] | [87] | Not assessed[88] | |

| Chilean jack mackerel | T. murphyi (Nichols, 1920) | 70 cm | 45 cm | kg | 16 years | 3.49 | [89] | [90] | ||

| Cunene horse mackerel | T. trecae (Cadenat, 1950) | 35 cm | cm | 2.0 kg | years | 3.49 | [92] | [93] | Not assessed | |

| Greenback horse mackerel | T. declivis (Jenyns, 1841) | 64 cm | 42 cm | kg | 25 years | 3.93 | [94] | [95] | Not assessed[96] | |

| Japanese horse mackerel | T. japonicus (Temminck & Schlegel, 1844) | 50 cm | 35 cm | 0.66 kg | 12 years | 3.4 | [97] | [98] | Not assessed | |

| Mediterranean horse mackerel | T. mediterraneus (Steindachner, 1868) | 60 cm | 30 cm | kg | years | 3.59 | [99] | [100] | Not assessed | |

| Pacific jack mackerel | T. symmetricus (Ayres, 1855) | 81 cm | 55 cm | kg | 30 years | 3.56 | [101] | |||

| Yellowtail horse mackerel | T. novaezelandiae (Richardson, 1843) | 50 cm | 35 cm | kg | 25 years | 4.5 | [103] | Not assessed | ||

| Gempylidae Snake mackerel | Black snake mackerel | Nealotus tripes (Johnson, 1865) | 25 cm | 15 cm | kg | years | 4.2 | [104] | Not assessed | |

| Blacksail snake mackerel | Thyrsitoides marleyi (Fowler, 1929) | 200 cm | 100 cm | kg | years | 4.19 | [105] | Not assessed | ||

| Snake mackerel | Gempylus serpens (Cuvier, 1829) | 100 cm | 60 cm | kg | years | 4.35 | [106] | Not assessed | ||

| Violet snake mackerel | Nesiarchus nasutus (Johnson, 1862) | 130 cm | 80 cm | kg | years | 4.33 | [107] | Not assessed | ||

| * White snake mackerel | Thyrsitops lepidopoides (Cuvier, 1832) | 40 cm | 25 cm | kg | years | 3.86 | [108] | Not assessed | ||

| Hexagrammidae | Okhotsk atka mackerel | Pleurogrammus azonus (Jordan & Metz, 1913) | 62 cm | cm | 1.6 kg | 12 years | 3.58 | [109] | [110] | Not assessed |

| Atka mackerel | P. monopterygius (Pallas, 1810) | 56.5 cm | cm | 2.0 kg | 14 years | 3.33 | [111] | Not assessed | ||

The term mackerel is also used as a modifier in the common names of other fish, sometimes indicating the fish has vertical stripes similar to a scombroid mackerel:

- Mackerel icefish—Champsocephalus gunnari

- Mackerel pike—Cololabis saira

- Mackerel scad—Decapterus macarellus

- Mackerel shark—several species

- Sharp-nose mackerel shark—Isurus oxyrinchus

- Mackerel tuna—Euthynnus affinis

- Mackerel tail goldfish—Carassius auratus

By extension, the term is applied also to other species such as the mackerel tabby cat,[112] and to inanimate objects such as the altocumulus mackerel sky cloud formation.[113]

Characteristics[edit]

Most mackerel belong to the family Scombridae, which also includes tuna and bonito. Generally mackerel are much smaller and slimmer than tuna, though in other respects they share many common characteristics. Their scales, if present at all, are extremely small. Like tuna and bonito, mackerel are voracious feeders, and are swift and manoeuvrable swimmers, able to streamline themselves by retracting their fins into grooves on their body. Like other scombroids, their bodies are cylindrical with numerous finlets on the dorsal and ventral sides behind the dorsal and anal fins, but unlike the deep-bodied tuna, they are slim.[114]

The type species for scombroid mackerels is the Atlantic mackerel, Scomber scombrus. These fish are iridescent blue-green above with a silvery underbelly and twenty to thirty near vertical wavy black stripes running across their upper body.[26][116]

It might seem that the prominent stripes on the back of mackerels are there to provide camouflage against broken backgrounds. That is not the case, because mackerel live in midwater pelagic environments which have no background.[117] However, fish have an optokinetic reflex in their visual systems which can be sensitive to moving stripes.[118] In order for fish to school efficiently, they need feedback mechanisms that help them align themselves with adjacent fish, and match their speed. The stripes on neighbouring fish provide "schooling marks" which signal changes in relative position.[117][119]

There is a layer of thin reflecting platelets on some of the mackerel stripes. In 1998, E J Denton and D M Rowe argued that these platelets transmit additional information to other fish about how a given fish moves. As the orientation of the fish changes relative to another fish, the amount of light reflected to the second fish by this layer also changes. This sensitivity to orientation gives the mackerel "considerable advantages in being able to react quickly while schooling and feeding."[120]

Mackerel range in size from small forage fish to larger game fish. Coastal mackerel tend to be small.[121]The king mackerel is an example of a larger mackerel. Most fish are cold-blooded, but there are exceptions. Certain species of fish maintain elevated body temperatures. Endothermic bony fishes are all in the suborder Scombroidei and include the butterfly mackerel, a species of primitive mackerel.[122]

Mackerel are strong swimmers. Atlantic mackerel can swim at a sustained speed of 0.98 metres/sec with a burst speed of 5.5 m/s,[123][124] while chub mackerel can swim at a sustained speed of 0.92 m/s with a burst speed of 2.25 m/s.[114]

Distribution[edit]

Most mackerel species have restricted distribution ranges.[114]

- Atlantic Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus) occupy the waters off the east coast of North America from the Cape Cod area south to the Yucatan Peninsula. Its population is considered to include two fish stocks, defined by geography. As summer approaches, one stock moves in large schools north from Florida up the coast to spawn in shallow waters off the New England coast. It then returns to winter in deeper waters off Florida. The other stock migrates in large schools along the coast from Mexico to spawn in shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico off Texas. It then returns to winter in deeper waters off the Mexican coast.[56] These stocks are managed separately, even though genetically they are identical.[57]

- The Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) is a coastal species found only in the north Atlantic. The stock on the west side of the Atlantic is largely independent of the stock on the east side. The stock on the east Atlantic currently operates as three separate stocks, the southern, western and North Sea stocks, each with their own migration patterns. Some mixing of the east Atlantic stocks takes place in feeding grounds towards the north, but there is almost no mixing between the east and west Atlantic stocks.[5][127][128][129][130]

- Another common coastal species, the chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus), is absent from the Atlantic Ocean but is widespread across both hemispheres in the Pacific, where its migration patterns are somewhat similar to those of Atlantic mackerel. In the northern hemisphere, chub mackerel migrate northwards in the summer to feeding grounds, and southwards in the winter when they spawn in relatively shallow waters. In the southern hemisphere the migrations are reversed. After spawning, some stocks migrate down the continental slope to deeper water and spend the rest of the winter in relative inactivity.[23]

- The Chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi), the most intensively harvested mackerel-like species, is found in the south Pacific from West Australia to the coasts of Chile and Peru.[89] A sister species, the Pacific jack mackerel (Trachurus symmetricus), is found in the north Pacific. The Chilean jack mackerel occurs along the coasts in upwelling areas, but also migrates across the open ocean. Its abundance can fluctuate markedly as ocean conditions change,[91] and is particularly affected by the El Niño.

Three species of jack mackerels are found in coastal waters around New Zealand: the Australasian, Chilean and Pacific jack mackerels. They are mainly captured using purse seine nets, and are managed as a single stock that includes multiple species.[131]

Some mackerel species migrate vertically. Adult snake mackerels conduct a diel vertical migration, staying in deeper water during the day and rising to the surface at night to feed. The young and juveniles also migrate vertically but in the opposite direction, staying near the surface during the day and moving deeper at night.[132] This species feeds on squid, pelagic crustaceans, lanternfishes, flying fishes, sauries and other mackerel.[133] It is in turn preyed upon by tuna and marlin.[134]

Life cycle[edit]

Mackerel are prolific broadcast spawners and must breed near the surface of the water due to the eggs of the females floating. Individual females lay between 300,000 and 1,500,000 eggs.[114] Their eggs and larvae are pelagic, that is, they float free in the open sea. The larvae and juvenile mackerel feed on zooplankton. As adults they have sharp teeth, and hunt small crustaceans such as copepods, as well as forage fish, shrimp and squid. In turn they are hunted by larger pelagic animals such as tuna, billfish, sea lions, sharks and pelicans.[24][41][135]

Off Madagascar, spinner sharks follow migrating schools of mackerel.[136] Bryde's whales feed on mackerel when they can find them. They use several feeding methods, including skimming the surface, lunging, and bubble nets.[137]

Fisheries[edit]

Chub mackerel, Scomber japonicus, are the most intensively fished scombroid mackerel. As can be seen from the graph on the right, they account for about half the total capture production of scombroid mackerels.[1]As a species they are easily confused with Atlantic mackerel. Chub mackerel migrate long distances in oceans and across the Mediterranean. They can be caught with drift nets and suitable trawls, but are most usually caught with surround nets at night by attracting them with lampara lamps.[138]

The remaining catch of scombroid mackerels is divided equally between the Atlantic mackerel and all other scombroid mackerels. Just two species account for about 75% of the total catch of scombroid mackerels.[1]

Chilean jack mackerel are the most commonly fished non-scombroid mackerel, fished as heavily as chub mackerel[1][90] (see second graph on the right). The species has been overfished, and its fishery may now be in danger of collapsing.[139][140]

Smaller mackerel behave like herrings, and are captured in similar ways.[141] Fish species like these, which schoolnear the surface, can be caught efficiently by purse seining. Huge purse seiner vessels use spotter planes to locate the schooling fish. Then they close in using sophisticated sonar to track the shape of the shoal. Entire schools are then encircled with fast auxiliary boats which deploy purse seine nets as they speed around the school.[142][143]

Suitably designed trollers can also catch mackerels effectively when they swim near the surface. Trollers typically have several long booms which they lift and drop with "topping lifts". They haul their lines with electric or hydraulic reels.[144] Fish aggregating devices are also used to target mackerel.[145]

| [show] Images and videos |

|---|

Management[edit]

The North Sea has been overfished to the point where the ecological balance has become disrupted and many jobs in the fishing industry have been lost.[146]

The Southeast US region spans the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea and the US Southeast Atlantic. Overfishing of king and Spanish mackerel occurred in the 1980s. Regulations were introduced to restrict the size, amount of catch, fishing locations and bag limits for recreational fishers as well as commercial fishers. Gillnetswere banned in waters off Florida. By 2001, the mackerel stocks had bounced back.[147]

As food[edit]

Mackerel is an important food fish that is consumed worldwide.[148] As an oily fish, it is a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids.[149]The flesh of mackerel spoils quickly, especially in the tropics, and can cause scombroid food poisoning. Accordingly, it should be eaten on the day of capture, unless properly refrigerated or cured.[150]

Mackerel preservation is not simple. Before the 19th-century development of canning and the widespread availability of refrigeration, salting and smoking were the principal preservation methods available.[151] Historically in England, this fish was not preserved, but was consumed only in its fresh form. However, spoilage was common, leading the authors of The Cambridge Economic History of Europe to remark: "There are more references to stinking mackerel in English literature than to any other fish!"[141] In France mackerel was traditionally pickled with large amounts of salt, which allowed it to be sold widely across the country.[141]