Inhibitory effect of Cantharidin on proliferation of A549 cells ...

Cantharidin hợp chất kháng A549

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

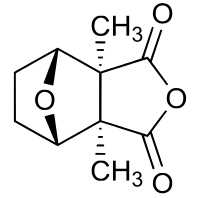

| IUPAC name

2,6-Dimethyl-4,10-dioxatricyclo-[5.2.1.02,6]decane-3,5-dione

| |

| Other names

Cantharidin, Spanish Fly

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

| |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.240 |

| KEGG | |

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| C10H12O4 | |

| Molar mass | 196.20 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.41 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 212 °C (414 °F; 485 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Highly toxic |

| GHS pictograms |  |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

| 0.03–0.5 mg/kg (human) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Infobox references | |

Cantharidin is an odorless, colorless terpenoid secreted by many species of blister beetles, including broadly in genus Epicauta, and in species Lytta vesicatoria (Spanish fly). False blister beetles, cardinal beetles, and soldier beetles also produce cantharidin. Poisoning from the substance is a significant veterinary concern, especially in horses from the Epicauta species, but it can also be poisonous to humans if taken internally (where the origin is most often experimental self-exposure). Externally, cantharidin is a potent vesicant (blistering agent), exposure to which can cause severe chemical burns. Properly dosed and applied, the same properties have been used for effective topical medications for some conditions, such as treating patients with Molluscum contagiosum infection of the skin.

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[1]

Contents

[hide]Chemistry[edit]

Structure and nomenclature[edit]

Cantharidin, from the Greek kantharis, for beetle,[2] is an odorless, colorless natural product with solubility in various organic solvents,[specify] but only slightly solubility in water.[3] It is a monoterpene, and so contains in its framework two isoprene units derived by biosynthesis from two equivalents of isopentenyl pyrophosphate.[4] The complete mechanism of the biosynthesis of cantharidin is unknown. Its skeleton is tricyclic, formally, a tricyclo-[5.2.1.02,6]decane skeleton. Its functionalities include an carboxylic acid anhydride (-CO-O-CO-) substructure in one of its rings, as well as a cyclic ether in its bicyclic ring system.

Distribution and availability[edit]

The level of cantharidin in blister beetles can be quite variable. Among blister beetles of the genus Epicauta in Colorado, E. pennsylvanica contains about 0.2 mg, E. maculata contains 0.7 mg, and E. immaculata contains 4.8 mg per beetle; males also contain higher levels than females.[5]

History[edit]

Cantharidin was first isolated in 1810 by Pierre Robiquet,[6] a French chemist then living in Paris, from Lytta vesicatoria. Robiquet demonstrated that cantharidin was the actual principle responsible for the aggressively blistering properties of the coating of the eggs of that insect, and established that cantharidin had definite toxic properties comparable in degree to those of the most virulent poisons known in the 19th century, such as strychnine.[7] It is an odorless and colorless solid at room temperature. It is secreted by the male blister beetle and given to the female as a copulatory gift during mating. Afterwards, the female beetle covers her eggs with it as a defense against predators.

There are many examples in historical sources that reference preparations of this natural product:

- According to Tacitus, it was used by the empress Livia, wife of Augustus Caesar to entice members of the imperial family or dinner guests to commit sexual indiscretions (thus providing her information to hold over them).[8]

- Henry IV (1050–1106) is said to have consumed Spanish fly.[9]

- In 1572, Ambroise Paré wrote an account of a man suffering from "the most frightful satyriasis" after taking a potion composed of nettles and cantharides.[10]

- In 1611, Juan de Horozco y Covarrubias reported the use of blister beetles as a poison and as an aphrodisiac.[11]

- In the 1670s, Spanish fly was mixed with dried mole's and bat's blood for a love charm made by the magician La Voisin.[12][clarification needed]

- Cantharides are reported to have become fashionable in the 18th century, e.g., being known as pastilles Richelieu in France,[citation needed] and are said to have been slipped into the food of Louis XIV to secure the king's lust for Madame de Montespan.[by whom?][dubious ][citation needed]

- The Marquis de Sade is said to have given aniseed-flavored pastilles laced with Spanish fly to two prostitutes at an orgy in 1772, poisoning and nearly killing them. He was sentenced to death for that, and sodomy, but later reprieved on appeal.[13][14]

Veterinary issues[edit]

Poisoning from catharidin is a significant veterinary concern, especially in horses by Epicauta species; species infesting feedstocks depend on region—e.g., Epicauta pennsylvanica (black blisterbeetle) in the U.S. midwest and E. occidentalis, temexia, and vittata species (striped blister beetles) in the U.S. southwest—where the concentrations of the agent in each can vary substantially.[3] Beetles feed on weeds and occasionally move into crop fields used to produce livestock feeds (e.g., alfalfa), where they are found to cluster and find their way into baled hay, e.g., a single flake (4-5 in. section[15]) may have several hundred insects, or none at all.[3]Horses are very sensitive to the cantharidin produced by beetle infestations: the LD50 for horses is roughly 1 mg/kg of the horse's body weight. Horses may be accidentally poisoned when fed bales of fodder with blister beetles in them.[16]

Great bustards, a strongly polygynous bird species,[17] are not immune to the toxicity of cantharidin; they become intoxicated after ingesting blister beetles; however, cantharidin has activity also against parasites that infect them.[18][19] Great bustards may eat toxic blister beetles of the genus Meloe to increase the sexual arousal of males.[20]

Human medical issues[edit]

General risks[edit]

As a blister agent, cantharidin has the potential to cause adverse effects when used medically; for this reason, it has been included in a list of "problem drugs" used by dermatologists[21] and emergency personnel.[22] However, when compounded properly and applied in the clinic topically by a medical provider familiar with its effects and uses, cantharidin can be safely and effectively used to treat some benign skin lesions like warts and molluscum.[23]

When ingested by humans, the LD50 is around 0.5 mg/kg, with a dose of as little as 10 mg being potentially fatal. Ingesting cantharidin can initially cause severe damage to the lining of the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts, and may also cause permanent renal damage. Symptoms of cantharidin poisoning include blood in the urine, abdominal pain, and rarely prolonged erections.[21]

Risks of aphrodisiac use[edit]

Cantharidin has been used since ancient times as an aphrodisiac, possibly because its physical effects were perceived to mimic those of sexual arousal,[24] and because it can cause priapism.[25] The extreme toxicity of cantharidin makes any use as an aphrodisiac highly dangerous.[26][27] As a result, it is illegal to sell (or use) cantharidin or preparations containing it without a prescription in many countries.[22]

Other uses[edit]

Diluted solutions of cantharidin can be used as a topical medication to remove warts[28][29] and tattoos and to treat the small papules of Molluscum contagiosum.[30]

Cantharides (the dried beetle) was historically considered to be an effective treatment for smallpox.[31] Andrew Taylor Still, the founder of osteopathy, in his 1892 book The philosophy and mechanical principles of osteopathy recommended inhaling tincture of cantharidin as an effective preventative and treatment, decrying vaccination.[32]

Research[edit]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Cantharidin is absorbed by the lipid membranes of epidermal cells, causing the release of serine proteases, enzymes that break the peptide bonds in proteins. This causes the disintegration of desmosomal plaques, cellular structures involved in cell-to-cell adhesion, leading to detachment of the tonofilaments that hold cells together. The process leads to the loss of cellular connections (acantholysis) and ultimately blistering of the skin. Lesions heal without scarring.[23][33]

Bioactivities[edit]

Cantharidin appears to have some effect in the topical treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in animal models.[34] In addition to topical medical applications, cantharidin and its analogues may have activity against cancer cells.[35][36][37] Laboratory studies with cultured tumor cells suggest that this activity may be the result of PP2A inhibition.[38][39]

Popular culture[edit]

Natural products preparations containing cantharidin appear frequently in popular media. Examples include:

- The I Spy, where Bill Cosby joked about co-star Robert Culp's having tried to obtain some when in Spain, where a Spanish cab driver responded to a request for it, asking them in turn for "American Fly" (emphasizing the idea of Spanish fly as a universal male fantasy).[40][41]

- The substance, extracted from the fictional Sudanese blister beetle, plays a pivotal role in Roald Dahl's novel My Uncle Oswald.

Further reading[edit]

- Dupuis, Gérard & Berland, Nicole (2004). "Cantharidin: Origin and synthesis," Lille, FR: Lycée Faidherbe, see [1], accessed 13 December 2015